Translated from French

A field open to men? Yes, but…

The statement that early childhood education in Canada is a field in which women are in the majority will surprise no one in 2024, and this has always been so. The care and raising of children are tasks that women have assumed over the years while men have worked and flourished in more lucrative sectors that are, in many cases, either traditionally male or reserved for men. However, when we look at this sex-based division of labour from a gender-equality standpoint, we quickly realize that something is not right.

Some men do work in early child education, despite social expectations that all too often exclude them. There are not many men in this field, but they are there, and they often generate some discussion. For one thing, they are encouraged and validated for their commitment to a traditionally female sector, especially since they are given to understand that their presence shatters deep-rooted gender stereotypes and that children need them for the positive male image they provide in the world of education. For another, they are singled out for being different and in the minority in a female environment: people question their reasons for working with children—they are often suspected of pedophilia, and they are sometimes tolerated as colleagues but not allowed to change a baby’s diapers. It is regularly made clear to them that the field is one that women have dominated with pride for many years, putting their hearts and much of their energy into it. Given these opposing positions that men confront on an almost daily basis, it is normal and legitimate to ask whether the early childhood education field is truly open to men.

As members of the Comité québécois pour la mixité en éducation à l’enfance [Quebec committee for co-ed early childhood education], we have been recently thinking about gender balance in early childhood education, and, more specifically, males with children in an occupational setting. After facilitating focus groups on the subject, and taken several steps to encourage men to register for our college-level early childhood education courses, we asked ourselves the following three questions:

- What attracts men to early childhood education?

- What retains male students in early childhood education training and keeps male early childhood educators on the job?

- How do we ensure that the men who devote themselves to this sector can find fulfilment in their work?

Attraction

The Universalis dictionary defines ‘attraction’ as a characteristic that draws people to a person or a thing, and charms them.[1] In light of this definition, we may question what attracts men to early childhood education, and where the charm lies in working with children.

We often ask the men we meet in our various activities why they work in early childhood education, and what they like about their work. In fact, those questions were the basic concept of our short film Éducateur à l’enfance, héros des petits, [Child educators: heroes in young children’s eyes], which is available on our website.[2] The answers are varied and all of them are interesting, but the one we get most often is the feeling of making a difference in children’s lives. Most answers relate to the feeling of doing a job that is essential to society and is important to a particular population, namely, children. One early childhood educator even compared the job to that of a gardener who enjoys watching the flowers they tend flourish.

For some men, there is considerable appeal in a job that requires them to be physically active and work outdoors. In this regard, Norwegian professor Leif Askland provided interesting information in the magazine Enfants d’Europe, on Norway’s plans to recruit and retain men in kindergartens (Askland, 2012). One thing he noted is that men are attracted more to kindergartens where the pedagogy emphasizes nature. “This format seems to attract more men than traditional kindergartens. It’s not usual to see these institutions have more than 30% men on their staff.” (Askland, 2012, p. 12). He adds that “men have a marked interest in nature, the outdoors, music, digital tools, photography, the arts, and physical education, and are more interested in kindergartens with a focus on specific pedagogical content.”

With respect to how early childhood education appeals to men, we absolutely have to look at what it is about this sector that does not attract them. Naturally, the world of early childhood education, and more specifically work as an early childhood educator, does not have a reputation for being particularly lucrative, at least in Quebec. Without making an exhaustive analysis of the situation, we do know that traditionally female occupations are often associated with vocations or natural roles that women have always performed in terms of taking care of children. Mike Marchal, the chairperson of AMEPE,[3] an organization in this field, and a doctoral candidate in the Office of the Mayor of Paris, speaks about the world of early childhood education as a socially unimportant relegation zone that mostly attracts women. “Based on a maternal model, and practised by women, these occupations can be thought of as an extension of the role of mothers into the public sphere.” (Marchal, 2015, p. 98). In both France and Quebec, the salaries of early childhood educators are not attractive, and do not reflect their importance in our society.

Another reason why men are not attracted to this occupation is what are called “social pressures.” By this we mean comments and non-verbal signals of disapproval that young men who show an interest in the field are subjected to—they are made to feel that it is not really a field for them. We have talked to a few men who came to early childhood education from a previous occupation that paid more. They admitted that in many cases when they were younger, their parents or close friends discouraged them from studying early child education.

The professional image this occupation projects is not inclusive in terms of gender, and therefore not very attractive to men. First, male early childhood educator models are few and far between. It is therefore difficult for a 16-year-old male to imagine himself becoming an early childhood educator if he has never in his life seen one, either in person or in a photograph.

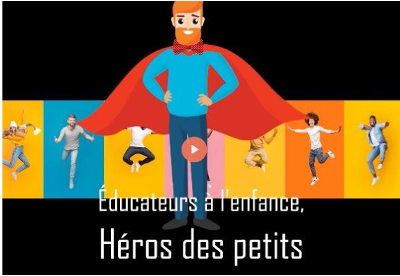

Second, job offers are often strongly oriented towards women, with the result that men do not feel that they are being included. Single-gender job offers[4] on social media reinforce the idea that this is an almost exclusively female field, providing arguments for people who exert social pressure on young males who show even a slight interest in early childhood education.

So how do we make early childhood education more attractive to men?

Combat social pressures

The verb “combat” here is not insignificant. When you take an interest in gender stereotypes and social pressures, and advocate equality, inclusion, and diversity in the workplace, you have to fight every day against preconceptions that impinge on everyone’s needs and wishes.

There are many ways of pushing back against social pressures, but they all involve communication. We have to talk about it with the people around us, ask questions of those who express ideas that seem outmoded to us, and never be afraid of expressing thoughts that might shock some people. We are in a struggle, after all!

Since Quebec’s Cégeps (College of General and Vocational Education) are teaching institutions that train most educational personnel, the members of early childhood education departments are well positioned to combat stereotypes and social pressures. For example, in January 2024, TEE[5] educators at the Cégep de l’Outaouais took part in a tour of high schools to meet with students and talk about the college’s early childhood educator program. In addition to presenting the TEE curriculum, discussions with students included the subject of gender equality, and the need for men, as well as women, to get involved in early childhood education. During open house days at Collège Montmorency in Laval, the subject was discussed with visitors. A booth on the subject of male presence in early childhood education was set up at a strategic location where passersby, regardless of any interest in the TEE program, could see that male students can study early childhood education and work with children.

Official documents relating to early childhood education are useful tools in the fight against gender stereotypes. In 2022, for example, the French Ministry of Labour, Health and Solidarity published a national charter for taking care of young children [Charte nationale pour l’accueil du jeune enfant]. This charter consisted of 10 cardinal principles that foster the development and fulfilment of children. Principle 7, part of the section on social diversity and inclusion, declares: “As a girl or boy, I need to be valued for my personal qualities, without regard for any stereotype. The same is true for the professionals who guide me. It is with the help of those women and men that I create my own identity.” (République Française, 2022).

Job offers that are inclusive and promote diversity

The Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse du Québec [Quebec human and youth rights commission] has published a handbook for employers entitled Recruter sans discriminer [Hire without discriminating]. In section 1 of this handbook, which deals with job offers, it is stated that one of the main elements to be included in such offers is the use of a gender-neutral job title. “Using a gender-neutral job title means making no reference to male or female gender.” (Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse du Québec, 2020, p. 6). Rather than using the wording “éducatrice à l’enfance recherchée” [looking for a female early childhood educator], it is better to use a neutral term to describe the position for which an employee is sought, such as “personnel éducateur” [educator]. Another approach would be to simply use a pair of terms: “éducatrice ou éducateur” [female or male educator]. These two ways of keeping things simple will make the job offer title inclusive and thus more attractive to men.

The content of a job offer can also harbour discrimination. In the fire safety field, for example, requiring that the candidate be “strong” could be wrongly perceived. What does it mean to be “strong”? Traditionally, strength has been associated with men and gentleness with women. The use of such terms thus silently discriminates against women who have an interest in potentially becoming a firefighter. To make such a job offer more inclusive, it would be better to indicate the precise minimum weight a person practising that occupation can lift, and in particular, in what circumstances. In early childhood education, indicating that a person must be gentle and caring can be discriminatory, given that men have not been traditionally recognized for such qualities. To make such an offer more inclusive, it would be better to list the tasks and expected professional skills and abilities entailed in the job.

Male role models

The Comité québécois pour la mixité has produced videos that show examples of men working with children in early childhood education settings. For example our video Éducateurs à l’enfance en action [Male early childhood educators in action], which runs a little under five minutes, presents male educators interacting with children in various settings. This video is used in recruiting activities to encourage men to register for early childhood education courses.

Another sound strategy is to use images of men working with children to demonstrate that this can also be a male occupation. The more images we see of men with children in magazines, on social media, or in promotional tools for study programs in early childhood education, the more such representation of men in that field will be possible. This strategy is also recommended by the GenderEYE[6] group in Lancaster, UK, to encourage men to work in the early childhood field (GenderEYE, 2020). It is even recommended that childcare facilities place images of men with children on their websites.

Retention

By the term “retention,” we mean keeping men in this field, that is to say, keeping male students in early childhood education training so that they can complete their studies, and then retaining male educators working or otherwise active in early childhood education.

We looked into the question of retention, because we noted that in Quebec colleges more men begin TEE studies than complete them. It is not unusual to see male students drop out of TEE programs, either to study Techniques d’éducation spécialisée (TES) [Special education techniques] or Sciences humaines [Human sciences] in order to become teachers, or move into a completely different field. After discussing with such students the choices they made, we assumed they had difficulty in seeing themselves in the field for the long term and did not feel they were entirely in the right place in training, even though they appreciated the contact with their young clients.

Following are some of the comments we heard from the students we spoke to:

” I am often the only guy in my classes, and I generally try to forget that, but unfortunately, the people around me are always reminding me of it.”

“My friends regularly ask me why I chose this course. They say that it is usually the girls who choose it.”

“Sometimes I can’t see myself in the examples provided in class.”

When talking to male early childhood educators on the job, we discovered that they showed a measure of uncertainty about their future in the field. Some of them told us they found it difficult being the only man where they worked, and said that they would appreciate being able to talk with a male colleague during the work day. Some confided that they had been victims of sexist and disagreeable jokes on the part of female colleagues, such as “men can’t do more than one thing at a time,” or “men lack sensitivity,” and they found such comments repetitive and tiresome. One member of the group deplored the fact that he could not work as many hours as he wished in his childcare centre, because members of the early childhood education staff could not work more than four days a week. He therefore had to work in a different field to make ends meet, which had made him think about changing jobs. Another told us that whenever he arranged his space differently to meet the children’s needs, his female colleagues put the furniture back as it was, without asking his opinion. Another male educator decided to leave the sector because the new female director of the centre where he worked monitored him constantly. He confided that she had given him a written warning to stop picking up the children and “flying” them to land on the floor after a diaper change. He had nevertheless been doing so earlier, before the arrival of the new director, and it had never been an issue. Another member of the focus group told us that he found it difficult to work as an early childhood educator from day to day, because the centre’s female director asked him not to guide the children as a man would, but rather to act more like a mother.

Relational care and diaper changes were a source of problems for all the male early childhood educators we spoke to during our online discussions. All of them had been requested not to change the diaper of one child in particular, at the request of the parents, or to do so only under close supervision. Many male early childhood educators have to deal with such requests year after year, because they are men. What is worse for them is when their female colleagues doubt the men’s ability to provide children with quality hygiene care on the grounds that men should not take care of babies, but should stay with the older children. On this point, researcher François Ndjapou discusses an interesting event in his article entitled “Le genre et la mixité en formation d’éducateur de jeunes enfants” [Gender and co-education in early childhood educator training](Ndjapou, 2014). A student on placement providing physical care to a six-month-old baby was told by a professional observing him to be less “virile” in his actions. This comment raised several questions in the student’s mind about masculinity and virility, and his own identity in this largely female field.

The confidences men shared with us during our online discussions, and on other occasions, surprised us and left their mark, giving us to understand that it was urgent to work on retaining men—both students and employees—in early childhood education. In the case of the students, the responsibility lies with TEE instructors, because they are the people working with them in the training environment. Using the male and female terms in French for early childhood educator [éducateur and éducatrice] is a good way of recognizing each gender, and using positive examples involving men would help men see themselves working in the profession. It is also recommended not to isolate men when addressing the group, since this merely emphasizes that they are in the minority. For example, instead of saying “Good morning, ladies and Robert,” it would be more appropriate to simply say “Good morning, everyone,” or just “Good morning.”

We train our students to act in an equitable manner with children, taking all human differences into consideration. We also teach them to show respect for human diversity in every area of human activity, and lastly, we urge them to consider inclusion as a personal crusade and an unquestioned objective, so that every child in the world is given their chance in life. The same crusade also applies to their work as early childhood educators. We must open the door, let them in, and give them an opportunity to be what they are: men who just want to support the overall development of children.

With respect to employment, responsibility for the retention of early childhood educators lies in part with management. Using neutral terminology in job offers is a recommended strategy to attract male applicants, as noted in the beginning of this article, but it is also a strategy for retaining those already on the job, as well as for showing respect. We also recommend that management pay attention to employee well-being, and be firm in dealing with discrimination against men. For example, if a family requests that an early childhood educator not change their baby’s diaper, instead of agreeing to the request, we believe that the family needs to receive guidance so that they realize that actions in a childcare facility are professional actions, for which both men and women have the needed skills.

In conclusion, on the subject of retention, we recommend that management treat men working in early childhood education in the same way they would hope women working in traditionally male sectors, like firefighting or construction, would be treated.

Fulfilment

From our viewpoint, fulfilment on the job means being comfortable in one’s environment, taking pride in one’s work and workplace, and feeling that one’s potential is being realized. Accordingly, the question to be asked in the context of our project to value the male presence in early childhood education can be broken down into three sub-questions:

- Do male early childhood educators feel comfortable in the workplace?

- Are men proud to say that they are early childhood educators?

- Do male early childhood educators feel that their potential is being realized?

A word about decorating the early childhood space

According to what men told us during our various activities, the males who feel comfortable in their early childhood space are those who can arrange and decorate their space as they wish. In some cases, perhaps many, the decoration of childcare facilities strongly favours elements often associated with the female sex, such as bumblebees, balloons, little flowers, pink children’s toys, and so on. For example, when a stocky man with a beard works in that kind of environment, the image produced may lead us to think that he is out of place, or even that he is uncomfortable in an environment that could be described as feminine. On the other hand, the image of the same man surrounded by a more neutral, less gender-focused décor would not produce the same visual effect. Thus the early childhood educator in question would not sense that an onlooker feels he is out of place working with children.[7]

Proud or not?

Pride in one’s work is often based on the comments one hears. Complimenting someone on the quality of their work or how they handle themselves is a good way of enhancing their self-esteem. If we want men to be proud to work in early childhood education, we have to tell them so. It is simply a matter of talking to them about the quality of their work, rather than their difference.

- Do male early childhood educators feel comfortable in the workplace?

- Are men proud to say that they are early childhood educators?

- Do male early childhood educators feel that their potential is being realized?

Fulfilment?

In the light of our encounters with men in this field, and our own reading on the subject, we have concluded that men have everything it takes to find fulfilment in this kind of work, providing only that they are allowed to do so. As men and women of today, we have not been brought up or socialized in the same way, with the result that people say we show “feminine” or “masculine” traits depending on our gender, with variations in intensity, of course. These differences are much more apparent when we work in the “other” field: a man working in a traditionally female field, such as a childcare centre, will appear different from his colleagues, just as a woman does as the only woman in a construction site team otherwise consisting of men. If we want such women and men, who dare to leave the well-trodden path, to find fulfilment in their work, they must be allowed to be what they are, without being forced to blend in with the majority.

Conclusion

in conclusion, we would like to direct your thoughts to three values that often serve as the background for our teaching in early childhood education techniques: equity, diversity, and inclusion. We train our students to act in an equitable manner with children, taking all human differences into consideration. We also teach them to show respect for human diversity in every area of human activity, and lastly, we urge them to consider inclusion as a personal crusade and an unquestioned objective, so that every child in the world is given their chance in life. The same crusade also applies to their work as early childhood educators. We must open the door, let them in, and give them an opportunity to be what they are: men who just want to support the overall development of children.

Bibliography

Askland, L. (2012, octobre). Égalité des sexes : recruter des hommes dans les jardins d’enfants. Enfants d’Europe, pp. 12-13.

Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse du Québec (2020). Recruter sans discriminer : Guide de l’employeur. https://www.cdpdj.qc.ca/storage/app/media/publications/Recruter-sans-discriminer_Guide.pdf

GenderEYE (2020). Gender Diversification of the Early Years Workforce : Recruiting, Supporting and Retaining Male Early Years Practitioners. Lancaster University: GenderEYE. parentinfantfoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Session1_02_Joann-Wilkinson.pdf

Germain, D., & St-Pierre, A. (2024). Mixité hommes. https://mixite-hommes.ca/

Marchal, M. (2015). Les institutions d’accueil de la petite enfance en France : Un espace social peu ouvert aux hommes et à l’égalité des sexes. Mouvements, pp. 97-105. shs.cairn.info/revue-mouvements-2015-2-page-97?lang=fr&tab=texte-integral

Ndjapou, F. (2014). Le genre et la mixité en formation d’éducateur(e) de jeunes enfants. Nouvelle revue de psychologie, p. 69 à 82. shs.cairn.info/revue-nouvelle-revue-de-psychosociologie-2014-1-page-69?lang=fr

République Française (2022). Charte nationale pour l’accueil du jeune enfant. solidarites.gouv.fr/charte-nationale-pour-laccueil-du-jeune-enfant Universalis (2024). Attirance. www.universalis.fr/dictionnaire/attirance/

[1] Universalis, 2024

[3] Agir pour la mixité et l’égalité en petite enfance [Taking action for co-education and equality in early childhood]

[4] Addressing only one gender—female, in this case.

[5] Techniques d’éducation à l’enfance [Early childhood education techniques]

[6] gendereye–findings–eop–final.pdf (wordpress.com)

[7] Photos from a Google search on the Web.

Author: Dominique Germain, teacher of early childhood education techniques and teacher of recreation management and activities, Collège Montmorency and Cégep de l’Outaouais

Co-author: Alain St-Pierre, teacher of early childhood education techniques, Collège Montmorency