By Jennifer Carr, Intiaz Khan, Alana Hunter, Alejandra Crich, Shamilah Mukhtar, and Dr. Sharon Quan-McGimpsey

Within Ontario, Canada, approximately 20% of children and youth experience a mental health challenge (Ontario Ministry of Child and Youth Services, 2018). While there is limited information regarding the prevalence of early childhood mental health challenges, it has been reported that 14-26% of children under six years of age meet the criteria for a mental health disorder within the United States of America (Egger & Arnold, 2006). The presence of mental health disorders in early childhood is significantly related to the existence of mental health disorders in primary school (Beyer, Postert, Muller, & Furniss, 2012). Furthermore, the presence of a mental health disorder in childhood or adolescence is a highly established precursor to the existence of a mental health disorder in adulthood (Fryers & Brugha, 2013). In this paper, early childhood mental health is defined as “the developing capacity of the child … to form close and secure adult and peer relationships; experience, manage, and express a full range of emotions; and explore the environment and learn – all in the context of family, community, and culture” (Zero to Three, 2016, p. 1).

Discover more of our ECE topics here

Despite the prevalence and predictive nature of early childhood mental health challenges, there appears to be varying levels of support for children with mental health challenges within early childhood education settings. When young children grow up with mental health challenges, parents are presented with unique experiences. This, in turn, has implications for early learning settings in which educators provide care for these children throughout the day. Numerous studies have demonstrated that early childhood educators (ECEs) often lack sufficient knowledge regarding early childhood mental health and appropriate prevention and intervention strategies (e.g., Davis et al., 2012; Giannakopoulos et al., 2014; Sims et al., 2012). Based upon a review of current research, there appears to be a lack of understanding regarding the parental experiences of early childhood mental health challenges.

An exploratory research study was designed with the purpose of describing the lived experience of five parents (18 to 49 years of age) with young children (14 months of age to 6 years of age) facing mental health challenges in relation to their involvement in early childhood education settings. No children discussed in this study had been formally diagnosed with a mental health disorder but were perceived to have challenges by their parents. This paper reports the findings (as reported in semi-structured individual interviews) of the interconnection between two phenomena, parenting and early childhood mental health challenges, with a focus on early education environments.

” We need a focus on early childhood mental health within professional development opportunities for educators . . . parents also require opportunities to voice their concerns about their children ”

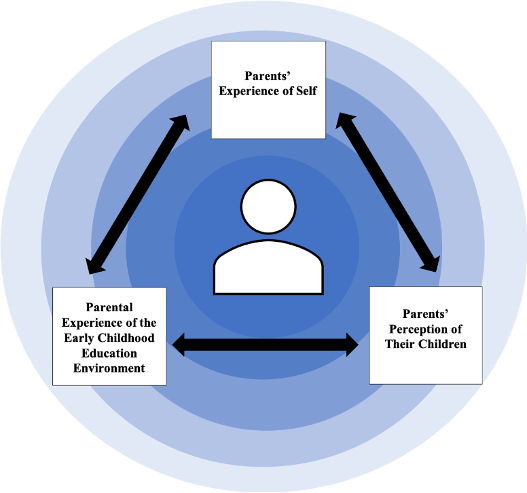

Parental Experience of the Early Childhood Education Environment

Parents expressed diverse experiences, including feeling a sense of support or lack of support for their children’s mental health challenges within the early childhood education environment. All parents discussed having positive relationships with at least one of their children’s educators regardless of the perceived level of support.

Parents who felt supported by ECEs reported having regular communication regarding their children’s behavior. In addition, educators sought to better support children with mental health challenges by seeking advice from other professionals. Parents shared that feeling supported involved having consistent, open lines of communication. For example, one parent noted, “We are constantly, on an ongoing basis with her talking about you know what kind of strategies she is using and we’re trying to keep [our strategies] consistent with what she’s doing.” Parents who felt supported also expressed that educators sought advice from other professionals to better support their children’s mental health needs. One parent shared his experience in stating that, “[The educator] talked to the principal and the principal gave her some information as well and then that was the case when we had to try to assure his self-esteem and it worked out well.”

Parents who felt a lack of support from their children’s ECEs expressed concerns regarding the educators’ lack of knowledge about early childhood mental health, including breadth and depth of information as well as the presentation of mental health challenges. Regarding a limited scope of understanding, one parent stated, “Most of them are just Registered ECEs and then I have my bachelor’s and a post-graduate certificate. So, like I feel like any information they may be able to give me, I already know.” Another parent shared how the home child care provider misunderstood her son’s presentation of mental health challenges and instead focused on enjoying the day with the children.

Whether parents felt supported or unsupported, they communicated that they had positive relationships with at least one of their children’s educators. Having ongoing communication as well as feeling heard and understood, were both found to be essential in having positive parent-educator relationships. One parent said, “I do have a good relationship with those teachers. They’re really open in terms of their language and what they say.” In addition, qualities such as being ‘honest’, ‘caring’, and ‘loving’ were attributed to the educators with whom the parents had positive relationships. Although parent-educator relationships were positive, how parents felt about themselves shows another side to their lived experience.

Parents’ Experience of Self

Parents discussed their self concept while raising children experiencing mental health challenges. Parents expressed two components of their self concept: the emotional response and the internalization of their children’s behaviour. One parent described her emotional response while sharing, “So apparently these outbursts are only happening at my house which makes me think I’m crazy sometimes.” The same parent discussed feeling embarrassed about her child’s behaviour and worried that her child would ‘swear’ in the early childhood education environment.

While discussing their children’s challenges with mental health, each parent noted how their own actions and behaviour may have contributed to their children’s current challenges. Some parents expressed a healthy level of self-awareness and self-reflection regarding how their parenting may have influenced their children; however, some parents demonstrated self-critical behaviour resulting in feelings of guilt and anxiety. Parents internalized their children’s behavior through stating how changes in their family dynamics might have aggravated or triggered their children’s mental health challenges. For example, one parent expressed, “I would say it started already when I started working full-time. So, about a half a year ago. And it got worse when we went for three and a half weeks to Germany.” Despite their misgivings about their internal perceptions of themselves, parents also acknowledged the need to be able to adapt the way they supported their children and the need to receive help from the ECEs on learning new strategies that would work better for their children. Keeping these feelings in mind, the parents still expressed positive perceptions of their children.

Parents’ Perception of Their Children

How parents perceived their children with mental health challenges was demonstrated within each interview. Specifically, parents reported early recognition of their children’s challenges with mental health and expressed a holistic view of their children.

All parents recognized their children’s mental health challenges before their children were two years of age. Specifically, one parent stated that he recognized his child’s challenges with mental health when he started attending an early childhood education environment. Although many parents stated that their children had previously or were currently being screened or assessed by the health care system, it was clarified that those assessments were not focused on social-emotional development. None of the children underwent a screening or assessment for their social-emotional development at their child care centre. One parent appeared surprised when asked whether her child had experienced any screenings or assessments at the child care centre by asking, “Do child cares even do that?”

All parents presented a holistic view of their children. Upon asking the parents about their children, their first responses consisted of their child’s abilities, positive traits, and interests despite their current challenges with mental health. Some of the words used to describe their children’s personalities included ‘funny’, ‘sweet’, ‘loving’, and ‘empathetic’. Multiple parents reported that their children had advanced academic abilities. For example, one parent stated, “She uses very complex sentences for her age and is interested in things that are a little bit too advanced for her age.” Instead of letting their children’s mental health challenges define them as individuals, each parent portrayed holistic understandings of their children which demonstrated the positive perception of these parent-child relationships.

Discussion

The findings of this study show that the lived experience of being a parent of a young child with mental health challenges is comprised of three components: parental experience of the early childhood education environment, parents’ experience of self, and parents’ perception of their children (Figure 1).

Each of these components seem to influence and be influenced by one’s relationships with others – all in the context of the social environment and time; therefore, the authors discuss the findings in relation to Hinde’s (2015) relationship theory. Hinde (2015) proposes a dialectical perspective to the study of relationships, in which he suggests that:

Relationships continually influence, and are influenced by their component interactions, and, thus, by the individual participants and by diverse psychological processes within those individuals; the groups and society in which they are embedded; the socio-cultural structure of beliefs, values, institutions and so on; and the social environment. (Frontispiece section, p. 2)

One key theme of this study is the experience of support versus lack of support. Two parents expressed feeling a lack of support for their children’s mental health challenges within the early childhood education environment. These findings support other research studies that suggest ECEs possess limited knowledge on the topic of early childhood mental health (Davis et al., 2012; Giannakopoulos et al., 2014; Sims et al., 2012). Yet, three parents expressed feeling well supported by their children’s educators; thus, highlighting the diverse parental experiences that may not be currently captured by research.

A deeper analysis of these findings was required. It is thought that the representations of relationships are communicated to ourselves, the relationship partner, and to others (Hinde, 2015). Each person has their own narrative regarding interactions with another person. When both partners are able to share their narrative of the interactions with the other, both narratives are brought in line together and mutual understanding occurs (Hinde, 2015). Within the current study, consistent and open discussion between the educator and parent regarding the child with mental health challenges resulted in the parent feeling a greater sense of support. Close relationships require individuals to engage in self-disclosure, yet self-disclosure requires a sense of trust (Hinde, 2015). The underlying contrast between a sense of support or non-support experienced by parents of children with mental health challenges may be related to the degree of trust felt towards others. If parental mistrust lies at the heart of the beliefs of some parents, it is imperative that early childhood environments work to find strategies to instill a sense of greater trust. Schweizer, Niedlich, Adamczyk, and Bormann (2017) argue that one crucial step in promoting greater trust between parents and educators is for both parties to clarify their roles – not only in rhetoric but in true actions to be taken.

A second key theme of this study is parents’ internalizations of their children’s challenges with mental health. Such internalizations and the associated emotional responses are not well understood in research. Hinde (2015) suggests that individuals hold theories about themselves, which influences behaviour, expectations for the future, and recollections of the past (which may be modified to maintain one’s self-concept). The inconsistencies reported in parents’ narratives depicting a constructive or contrary view of themselves may result from the different theories the parents hold.

Recommendations

In recognition of this study’s findings, the authors propose three recommendations. Firstly, there should be an increased focus on early childhood mental health within professional development opportunities for educators. By increasing ECEs’ knowledge of early childhood mental health, educators will be better able to support children with mental health challenges and their parents. Secondly, ECEs should schedule more occasions for parents and educators to engage in open and honest discussions about each of their roles and expectations of each other. Parents also require opportunities to voice their concerns about their children, which may include written and face-to-face platforms. Thirdly, further research is needed to explain the inconsistencies reported in parents’ narratives depicting a constructive or contrary view of themselves as a parent as well as supported versus unsupported views of the early childhood education environments.

Corresponding Author: Jennifer Carr, RECE,Honours Bachelor of Child Development Graduate, School of Early Childhood Education, Seneca College of Applied Arts and Technology, Toronto, Ontario

Intiaz Khan, Senior Honours Bachelor of Child Development Candidate, School of Early Childhood Education, Seneca College of Applied Arts and Technology, Toronto, Ontario

Alana Hunter, Senior Honours Bachelor of Child Development Candidate, School of Early Childhood Education, Seneca College of Applied Arts and Technology, Toronto, Ontario

Alejandra Crich, Senior Honours Bachelor of Child Development Candidate, School of Early Childhood Education, Seneca College of Applied Arts and Technology, Toronto, Ontario

Shamilah Mukhtar, Senior Honours Bachelor of Child Development Candidate, School of Early Childhood Education, Seneca College of Applied Arts and Technology, Toronto, Ontario

Dr. Sharon Quan-McGimpsey, Professor, School of Early Childhood Education, Seneca College of Applied Arts and Technology, Toronto, Ontario

The Lived Experience of Being a Parent of a Young Child with Mental Health Challenges

References

Beyer, T., Postert, C., Muller, J., & Furniss, T. (2012). Prognosis and continuity of child mental health problems from preschool to primary school: Results of a four-year longitudinal study. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 43(4), 533-543. doi:10.1007/s10578-012-0282-5

Davis, E., Priest, N., Davies, B., Smyth, L., Waters, E., Herrman, H, . . . Williamson, L. (2012). Family day care educators: An exploration of their understanding and experiences promoting children’s social and emotional wellbeing. Early Child Development and Care, 182(9), 1193-1208. doi:10.1080/03004430.2011.603420

Egger, H. L., & Angold, A. (2006). Common emotional and behavioural disorders in preschool children: Presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(3), 313-337. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01618.x

Fryers, T., Brugha, T. (2013). Childhood Determinants of adult psychiatric disorder. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, 9, 1-50. doi:10.2174/1745017901309010001

Giannakopoulos, G., Agapidaki, E., Dimitrakaki, C., Oikonomidou, D., Petanidou, D., Tsermidou, L., . . . Papadopoulou, K. (2014). Early childhood educators’ perceptions of preschoolers’ mental health problems: A qualitative analysis. Annals of General Psychiatry, 13(1), 1. doi:10.1186/1744-859X-13-1

Ontario Ministry of Child and Youth Services. (2018). Moving on mental health: A system that makes sense for children and youth. Retrieved from http://www.children.gov.on.ca/htdocs/English/professionals/specialneeds/momh/moving-on-mental-health.aspx

Hinde, R. A. (2015). Relationships: A dialectical perspective. [Kobo Aura One version]. Retrieved from www.kobo.com

Schweizer, A., Niedlich, S., Adamczyk, J., & Bormann, I. (2017). Approaching trust and control in parental relationships with educational institutions. Studia paedagogica, 22(2) 97-115.

Sims, M., Davis, E., Davies, B., Nicholson, J., Harrison, L., Herrman, H., . . . & Priest, N. (2012). Mental health promotion in childcare centres: Childcare educators’ understanding of child and parental mental health. Advances in Mental Health, 10(2), 138-148. doi:10.5172/jamh.2011.10.2.138

Zero to Three. (2016). Making it happen: Overcoming barriers to providing infant-early childhood mental health. Retrieved from https://www.zerotothree.org/resources/511-making-it-happen-overcoming-barriers-to-providing-infant-early-childhood-mental-health